Taxila, located just 35 kilometers northwest of Islamabad in the Punjab province of Pakistan, is one of the most compelling archaeological cities in South Asia. Its significance stretches far beyond its ruins—it represents a confluence of civilizations, philosophies, and artistic traditions that shaped the cultural landscape of the Indian subcontinent. For travelers, historians, and cultural enthusiasts, Taxila offers a rare opportunity to walk through the remnants of empires that once defined the ancient world.

Some Interesting Facts About Taxila

- The city’s name, derived from the Sanskrit word “Takṣaśilā,” meaning “City of Cut Stone,” hints at its ancient roots. Taxila was not just a city—it was a thriving intellectual hub, home to one of the earliest universities in recorded history. Scholars like Pāṇini, the father of Sanskrit grammar, and Kautilya, the political strategist behind the Mauryan Empire, are believed to have studied or taught here. This legacy of learning and philosophical inquiry is embedded in the very soil of Taxila.

- Taxila’s historical timeline is layered and complex. The earliest traces of human settlement date back to the Neolithic period, with the Saraikala site offering evidence of habitation as early as 3000 BCE. During the 6th century BCE, the city became a satrapy under the Achaemenid Empire, integrating Persian administrative and cultural influences. In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great arrived in Taxila, welcomed peacefully by King Ambhi. This encounter marked the beginning of Hellenistic influence, which would later merge with Buddhist traditions to create the distinctive Greco-Buddhist art of the Gandhara civilization.

- Under Mauryan rule, particularly during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, Taxila flourished as a center of Buddhist thought and architecture. Stupas, monasteries, and inscriptions from this era reflect a society deeply engaged in spiritual and intellectual pursuits. The Dharmarajika Stupa, believed to house relics of the Buddha, stands as a testament to this golden age. Later, the city saw waves of Scythian, Parthian, and Kushan rulers, each leaving behind architectural and cultural imprints that contribute to Taxila’s rich archaeological tapestry.

- Today, Taxila is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a designation that underscores its global importance. The ruins of Bhir Mound, Sirkap, and Sirsukh offer insights into ancient urban planning, trade networks, and religious practices. The Taxila Museum, with its extensive collection of Gandharan sculptures, coins, and pottery, provides a curated glimpse into the city’s multifaceted history. Visitors can trace the evolution of Buddhist iconography, observe the fusion of Greek and South Asian artistic styles, and appreciate the craftsmanship that defined an era.

- Beyond its historical allure, Taxila holds contemporary relevance. It serves as a symbol of Pakistan’s diverse heritage, where Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, and Hellenistic traditions once coexisted. For modern travelers, the city offers a chance to engage with history not as passive observers but as active participants in a shared cultural legacy. Walking through its ancient streets, one can imagine the bustling markets, the scholarly debates, and the spiritual rituals that once animated this vibrant metropolis.

- Taxila’s accessibility from Islamabad makes it an ideal destination for day trips, but its depth rewards those who choose to explore more thoroughly. Whether you’re a researcher delving into ancient texts, a photographer capturing the interplay of light and stone, or a cultural enthusiast seeking stories that transcend time, Taxila invites you to pause, reflect, and connect with the past.

How to Reach Taxila: Transportation Guide for Travelers

From Islamabad: The Quickest Route to Taxila

Taxila is just 35 kilometers northwest of Islamabad, making it one of the most accessible heritage sites in Pakistan. The fastest route is via Margalla Avenue or the Grand Trunk (GT) Road, with a typical drive taking 35 to 45 minutes depending on traffic. Travelers can use:

- Private Car or Taxi: Ideal for flexibility and comfort. Ride-hailing apps like Careem and InDrive offer one-way or hourly bookings.

- Local Buses and Vans: Available from Rawalpindi Saddar and Islamabad’s Faizabad terminal. These are budget-friendly but may require short rickshaw rides to reach specific ruins.

- Tour Packages: Several Islamabad-based tour operators offer guided day trips to Taxila, including transport, museum entry, and site commentary.

From Lahore: Long-Distance Options

Lahore is approximately 311 kilometers from Taxila. Travelers have multiple options:

- By Car: A direct drive via the M2 Motorway takes around 4 to 5 hours. This route offers scenic views and rest stops.

- Intercity Buses: Services like Daewoo, Faisal Movers, and Skyways run hourly buses to Islamabad. From there, switch to local transport or hire a taxi to Taxila. Total travel time: 5 to 6 hours.

- By Train: Pakistan Railways offers trains from Lahore to Rawalpindi. From Rawalpindi Station, Taxila is a short drive away. This option is slower but offers a nostalgic experience.

By Air: Fast but Less Practical

Flying is suitable for travelers short on time or arriving from distant cities:

- Lahore to Islamabad Flights: Offered by Airblue, Fly Jinnah, and PIA. Flight time is about 1 hour.

- Airport Transfer: Islamabad International Airport is roughly 50 kilometers from Taxila. Taxis and app-based rides are available at the terminal.

Local Transport Within Taxila

Once in Taxila, local mobility is straightforward:

- Rickshaws and Taxis: Available near the museum and main bazaar. Negotiate fares in advance.

- Walking Tours: Many sites are within walking distance of each other, especially around the museum and Bhir Mound.

- Guided Tours: Hiring a local guide enhances the experience with historical context and site navigation.

Travel Tips for Visitors

- Start Early: Sites open around 9 AM. Starting early helps avoid midday heat and crowds.

- Carry Essentials: Water, sunscreen, and comfortable shoes are recommended.

- Plan Site Clusters: Group nearby sites (e.g., Taxila Museum, Bhir Mound, Dharmarajika Stupa) to optimize time.

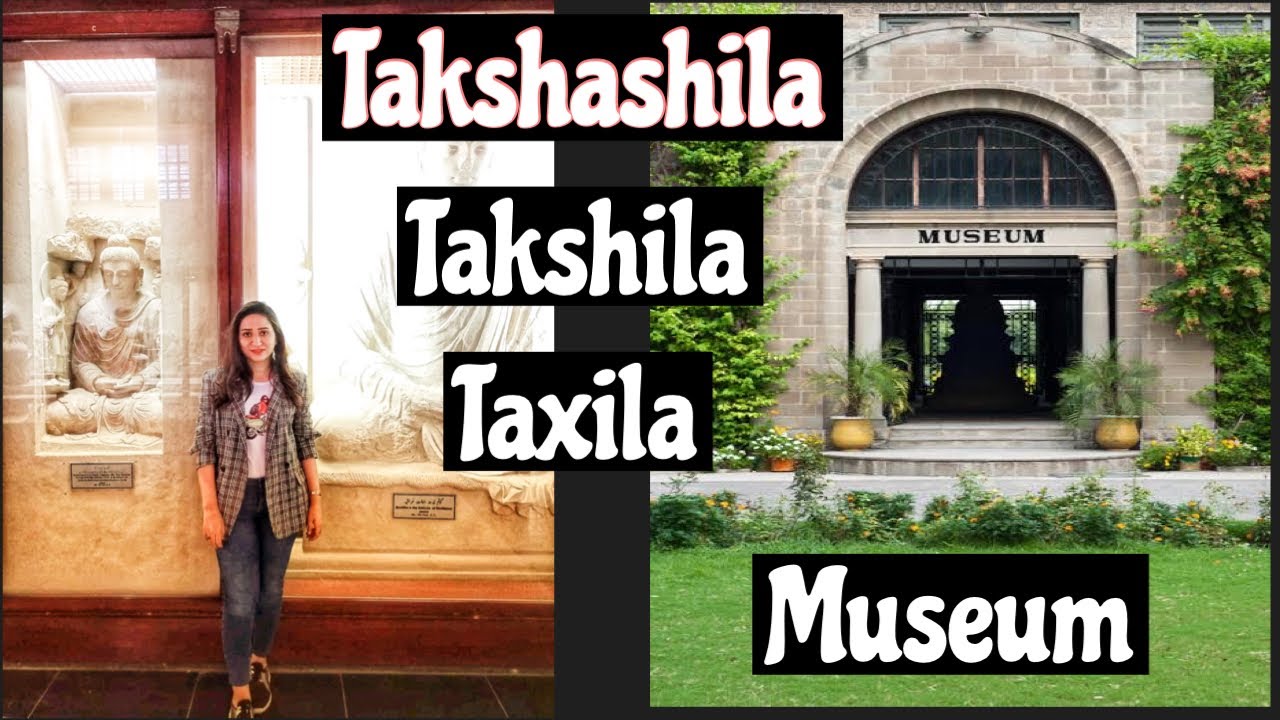

Taxila Museum: Gateway to the Gandhara Civilization

The Taxila Museum stands as the intellectual and artistic heart of the ancient city. Located just a short walk from Bhir Mound, this museum is more than a repository—it’s a curated journey through centuries of cultural evolution. For travelers, researchers, and heritage enthusiasts, it offers a rare opportunity to engage directly with the material legacy of the Gandhara civilization and the broader historical tapestry of Taxila.

Founded in 1918 and officially inaugurated in 1928 by Lord Chelmsford, the then Viceroy of British India, the museum was built to house the extraordinary discoveries unearthed during archaeological excavations led by Sir John Marshall. Its architecture reflects colonial-era design, with a central hall flanked by galleries that now contain over 7,000 artifacts spanning from the 1st to 7th centuries AD.

Inside, the museum’s galleries are organized chronologically and thematically, allowing visitors to trace the evolution of Gandharan art, Buddhist iconography, and daily life in ancient Taxila. The collection includes stone and terracotta sculptures, ancient coins, jewelry, pottery, tools, and inscriptions. Each item is meticulously labeled, often with bilingual descriptions in English and Urdu, enhancing accessibility for both local and international visitors.

One of the museum’s most striking features is its collection of Greco-Buddhist sculptures. These pieces, carved from schist stone, depict serene Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and narrative reliefs that blend Hellenistic realism with Buddhist symbolism. The folds of robes, the curls of hair, and the expressions of tranquility reflect a unique artistic synthesis that flourished in the Gandhara region. These sculptures are not merely decorative—they represent a philosophical and aesthetic dialogue between East and West.

Beyond religious art, the museum showcases everyday objects that offer insight into ancient lifestyles. Metallic cookware, grooming items, and decorative pieces reveal the sophistication of domestic life. Ancient coins from various dynasties—Achaemenid, Indo-Greek, Kushan—highlight Taxila’s role as a commercial hub. Jewelry exhibits, featuring gold and silver ornaments inlaid with semi-precious stones, speak to the craftsmanship and affluence of the region’s elite.

For scholars and students, the museum serves as a primary source for understanding Gandharan chronology and iconography. Many of the artifacts were excavated from nearby sites such as Jaulian, Mohra Moradu, and Dharmarajika, creating a direct link between the museum’s displays and the ruins scattered across Taxila. This contextual continuity makes the museum an essential stop for anyone seeking a holistic understanding of the region’s archaeological landscape.

The museum also plays a vital role in heritage preservation and education. It regularly hosts exhibitions, lectures, and school visits, fostering public engagement with Pakistan’s ancient history. Its proximity to other major sites allows visitors to pair their museum experience with on-ground exploration, creating a layered and immersive itinerary.

Practical information for visitors is straightforward. The museum is open daily from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM in winter and from 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM in summer, except on the first Monday of each month and Islamic holidays. Entry fees are modest: Rs. 100 for adults, Rs. 50 for children, and Rs. 500 for foreign tourists. Photography is allowed in most areas, though flash use may be restricted to preserve delicate artifacts.

Located on the Kalabagh-Nathia Gali Road (N-125), the museum is easily accessible by car, taxi, or local transport. It’s just a five-minute drive from Taxila’s railway station and surrounded by shops, restaurants, and basic amenities. For those planning a full-day visit, the museum makes an excellent starting point before heading to nearby ruins.

Dharmarajika Stupa: The Sacred Heart of Ancient Taxila

Just over three kilometers east of the Taxila Museum lies the Dharmarajika Stupa, a monumental Buddhist complex that once stood as the spiritual nucleus of the Gandhara region. Built in the 3rd century BCE by Emperor Ashoka, this stupa is believed to enshrine relics of Gautama Buddha himself, making it one of the earliest and most revered Buddhist sites in South Asia.

The name Dharmarajika is derived from “Dharmaraja,” a title associated with the Buddha as the Lord of Law. It also reflects Ashoka’s own spiritual transformation and his mission to spread Buddhism across his empire. Locally, the site is known as Chir Tope, or “Scarred Hill,” a reference to its weathered appearance and the centuries of history etched into its stones.

The Dharmarajika complex is divided into two main zones: the stupa area and the monastic quarters. The central stupa, built on a circular plan, measures approximately 131 feet in diameter and rises 45 feet high. Constructed from solid masonry, it features a raised terrace accessed by four staircases, and an open paved path around its base that once served as a procession route for pilgrims. Surrounding the main stupa are dozens of smaller votive stupas, chapels, and shrines, many of which were added between the 1st century BCE and the 5th century CE. These structures are adorned with Buddha figurines, floral motifs, and symbolic carvings that reflect the artistic evolution of Gandharan Buddhism.

To the north of the stupa lies the monastic area, which once housed the living quarters and meditation halls for monks. Excavations have revealed remnants of cells, kitchens, and assembly spaces, offering a glimpse into the daily life of the monastic community. The layout suggests a well-organized spiritual center, where learning, worship, and communal living coexisted in harmony.

One of the most remarkable discoveries at Dharmarajika was a silver reliquary containing a scroll that documented the enshrinement of Buddha’s relics. In 1917, a casket was unearthed from one of the chapels, believed to contain sacred relics of the Buddha. These were later gifted to the Buddhist community of Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) and are now enshrined in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy—a powerful testament to the site’s enduring spiritual legacy.

Historically, Dharmarajika has witnessed cycles of prosperity and devastation. After flourishing under the Mauryan and Kushan empires, the site suffered during the invasions of the White Huns in the 5th century CE. Under the rule of Mihirakula, a Hun king known for his persecution of Buddhists, thousands of monasteries across Gandhara were destroyed, including parts of Dharmarajika. Despite this, the site remained a pilgrimage destination for centuries and continues to attract visitors seeking historical insight and spiritual reflection.

For modern travelers, Dharmarajika offers a serene and contemplative experience. The site is surrounded by quiet hills and shaded paths, ideal for walking tours and photography. Informational plaques and guided tours help visitors understand the architectural features and historical significance of each structure. The absence of commercial noise enhances the meditative atmosphere, making it a favorite among cultural tourists and researchers.

Reaching Dharmarajika is straightforward. It’s located off PMO Colony Road, near the ancient city of Sirkap and northeast of Taxila Cantonment. Local rickshaws and taxis from the museum or railway station can take you there in under 10 minutes. Entry is free, though donations for site maintenance are welcome.

Jaulian Monastery: The Seat of Saints and Scholars

Perched atop a hill overlooking the lush valley of Taxila, Jaulian Monastery is a masterwork of ancient Buddhist architecture and spiritual devotion. Built in the 2nd century CE during the Kushan period, Jaulian was more than a religious site—it was a thriving center of learning, meditation, and artistic expression. Often referred to as the “Seat of Saints,” this monastic complex is considered one of the oldest universities in the world, where monks lived, studied, and taught the principles of Buddhism to disciples from across Asia.

The location of Jaulian is strategic and serene. Rising 100 meters above the modern village of Jaulian, the site offers panoramic views of the surrounding hills and plains. Its elevation not only provided natural defense but also symbolized spiritual ascent—a place removed from worldly distractions, ideal for contemplation and scholarly pursuit. The cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad lie just 35 to 45 kilometers away, making Jaulian easily accessible for modern travelers seeking a deep dive into Gandharan heritage.

The architectural layout of Jaulian is both functional and symbolic. The complex is divided into two main quadrangles surrounded by monastic living quarters. These include 28 student cells, a kitchen, storerooms, and an assembly hall, all constructed with baked bricks and lime mortar. The central courtyard houses the main stupa, surrounded by 27 smaller stupas and 59 chapels that depict scenes from the life of Buddha. These chapels are adorned with stucco reliefs and statues, many of which retain their original plaster and detailing despite centuries of exposure.

One of Jaulian’s most intriguing features is the “Healing Buddha,” a statue housed within a votive stupa that has a hole in its navel. Pilgrims and visitors often place their fingers in the cavity while offering prayers for healing. An inscription beneath the statue, dating back to the 5th century CE, suggests it was donated by a Buddhist friar, adding a layer of devotional history to the site’s spiritual significance.

The artistry at Jaulian reflects the fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist aesthetics typical of the Gandhara region. While the decorative quality is considered slightly less refined than that of nearby Mohra Moradu, the sculptures at Jaulian still convey profound serenity and narrative depth. The use of stucco allowed for intricate detailing, and many of the Buddha figures exhibit classical features—wavy hair, draped robes, and meditative expressions—that echo Greek artistic influence.

Jaulian’s decline began in the mid-5th century CE, when the White Huns invaded the region. Under the rule of Mihirakula, a Hun king notorious for his persecution of Buddhists, the monastery was attacked and eventually abandoned. Despite the destruction, the site remained a symbol of resilience and spiritual endurance. Excavations led by Sir John Marshall in the early 20th century revealed the full extent of Jaulian’s historical and architectural significance, and the site was officially inscribed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage listing for Taxila in 1980.

For visitors today, Jaulian offers a quiet, contemplative experience. The site is less crowded than other ruins in Taxila, allowing for uninterrupted exploration. Informational plaques and guided tours provide context, while the elevated terrain offers excellent opportunities for photography and reflection. The walk up to the monastery is moderately steep but manageable, and the surrounding landscape adds to the sense of isolation and tranquility that defines the site.

Jaulian is located near Khanpur Taxila Road, close to other notable ruins such as Mohra Moradu, Sirsukh, and Badalpur Stupa. Local transport options include rickshaws and taxis from the Taxila Museum or railway station. Entry is free, though donations for site preservation are encouraged.

Mohra Moradu: A Hidden Gem of Gandharan Spirituality

Tucked into a quiet glen just a few kilometers southeast of the Taxila Museum, Mohra Moradu is a remarkably well-preserved Buddhist monastery and stupa complex dating back to the 2nd century CE. Often overshadowed by more prominent sites like Jaulian and Dharmarajika, Mohra Moradu offers a tranquil, immersive experience for travelers and researchers seeking a deeper understanding of Gandharan architecture, monastic life, and spiritual practice.

The site was excavated between 1914 and 1915 under the supervision of Sir John Marshall, with Abdul Qadir leading the fieldwork. What emerged from beneath centuries of earth and vegetation was a two-part complex: a central stupa surrounded by votive stupas, and an adjacent monastery built around a square courtyard. Despite damage from treasure hunters—who split open the main stupa in search of gold—the lower portions remained protected by natural sediment, preserving many of the original stucco reliefs and architectural features.

The main stupa stands on a raised platform over 4.75 meters high, with a circular base and a square terrace. Its surface is adorned with bas-reliefs depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha, including his birth, enlightenment, and first sermon. These carvings, executed in stucco, retain traces of their original pigments—faint yellows, crimsons, and blues—that hint at the vibrant aesthetic of ancient Gandharan art. Surrounding the main stupa are smaller votive stupas, some dedicated to revered monks and teachers. One such monument, located within a monastic cell, rises four meters high and was once topped with painted umbrellas, symbolizing spiritual protection and reverence.

The monastery itself is a textbook example of Gandharan design. It consists of 27 rooms arranged around a central courtyard, which features a square ritual pool used for ablutions and rainwater collection. The pool is accessible via staircases on all sides and is still partially functional today. The monastery also includes a kitchen, a refractory, an assembly hall, and a well—elements that reflect the self-sustaining nature of monastic life. Statues of the Buddha are found throughout the complex, placed in niches and chapels, each reflecting different mudras (hand gestures) and iconographic styles.

One of Mohra Moradu’s most distinctive features is its architectural layering. The monastery was originally a two-story structure, with staircases leading to the upper level and wooden extensions connecting different sections. The strength of the walls suggests the possibility of a third story, though no definitive evidence has been found. This verticality, combined with the site’s secluded location, created an ideal environment for meditation, study, and spiritual retreat.

Historically, Mohra Moradu functioned as a satellite institution to larger centers like Jaulian. Its proximity to the ancient city of Sirsukh—just 1.5 kilometers away—allowed monks to engage in alms rounds while maintaining a peaceful distance from urban distractions. The site’s layout and artifacts suggest a vibrant intellectual and devotional community, with strong ties to the broader Buddhist network of the Gandhara region.

For modern visitors, Mohra Moradu offers a quiet alternative to the more frequented ruins of Taxila. The site is surrounded by natural beauty—rolling hills, shaded paths, and panoramic views—that enhance its contemplative atmosphere. It’s ideal for photography, sketching, and reflective walks. Informational plaques and guided tours are available, though the site’s serenity often speaks for itself.

Accessing Mohra Moradu is straightforward. It’s located off Khanpur Road, near the village of Mohra Moradu, and is reachable by rickshaw or taxi from the Taxila Museum or railway station. Entry is free, and the site is open daily from morning until dusk. Visitors are encouraged to bring water, wear comfortable shoes, and respect the sanctity of the ruins.

Sirkap: The Indo-Greek City of Grid and Stone

Sirkap is one of the most fascinating archaeological sites in Taxila, offering a rare glimpse into the urban planning and cultural fusion of the Indo-Greek period. Founded around 180 BCE by the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius, Sirkap was built after his conquest of the region and served as the second major urban center of Taxila, following the earlier settlement at Bhir Mound. What sets Sirkap apart is its distinctly Hellenistic layout—a grid-based city plan that reflects the influence of Greek urban ideals transplanted into South Asia.

The city was constructed using the Hippodamian grid system, a hallmark of classical Greek architecture. It featured one main avenue running north to south, intersected by fifteen perpendicular streets, creating a network of rectangular blocks. This design was a radical departure from the organic layouts of earlier South Asian cities and signaled a new era of administrative and architectural sophistication. The city spanned approximately 1,200 by 400 meters and was enclosed by a fortified wall nearly five kilometers long and up to seven meters thick.

Sirkap’s ruins reveal a cosmopolitan society where Greek, Indian, Scythian, and Parthian influences coexisted. Excavations have uncovered residential quarters, temples, stupas, and marketplaces, each reflecting a blend of artistic and cultural traditions. One of the most iconic structures is the Double-Headed Eagle Stupa, a unique monument that combines Buddhist symbolism with Hellenistic motifs. The stupa features a double-headed eagle flanked by lions and elephants—an emblem that likely represented power, protection, and spiritual transcendence.

The city also housed a variety of religious buildings, including Jain temples, Buddhist stupas, and Hindu shrines. This diversity underscores Sirkap’s role as a melting pot of spiritual traditions. Archaeological finds include stone palettes depicting Greek mythological scenes, coins from Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian rulers, and terracotta figurines that reflect local craftsmanship. These artifacts are now housed in the Taxila Museum, providing a tangible link between the ruins and the broader narrative of Gandharan civilization.

Sirkap’s history is layered. After its initial construction by Demetrius, the city was expanded and rebuilt by King Menander I, another prominent Indo-Greek ruler known for his conversion to Buddhism. Later, the city came under the control of Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian dynasties, each contributing to its architectural and cultural evolution. By the 1st century CE, however, Sirkap began to decline, eventually overshadowed by the newer city of Sirsukh, built by the Kushans.

Despite its decline, Sirkap remains a vital archaeological site. Excavations led by Sir John Marshall between 1912 and 1930, and later by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1940s, revealed only a fraction of the city’s full extent. Much of the Indo-Greek strata remains unexplored, suggesting that future digs could uncover even more about the city’s role in ancient trade, governance, and religious life.

For modern visitors, Sirkap offers a compelling experience. The site is located just off Khanpur Dam Road, a short drive from the Taxila Museum. It’s open daily from morning until dusk, with no entry fee. The ruins are spread across a wide area, so comfortable walking shoes and water are recommended. Informational plaques guide visitors through key structures, and local guides are available for deeper historical context.

Sirkap is ideal for photography, sketching, and immersive exploration. The symmetry of its streets, the elegance of its ruins, and the quietude of its surroundings make it a favorite among cultural tourists and academic researchers. It’s also a prime example of how ancient cities adapted foreign architectural principles to local needs, creating a hybrid urban identity that still resonates today.

Sirsukh: The Kushan Legacy of Fortified Urbanism

Sirsukh represents the last great urban chapter in the ancient history of Taxila. Founded during the Kushan period after 80 CE, this city was built to replace the older Indo-Greek settlement of Sirkap. Unlike its predecessors, Sirsukh was designed with defense and imperial grandeur in mind, reflecting the Kushans’ strategic priorities and architectural innovations. Today, its massive walls and untouched interior offer a haunting glimpse into a city that once thrived but was never fully excavated.

The city’s layout is rectangular, stretching approximately 1,500 meters north to south and 1,100 meters east to west. It was enclosed by a formidable wall built with stone and lime mortar, measuring up to five meters thick and seven meters high in places. This fortification was not just symbolic—it was functional, designed to protect the city from external threats and assert Kushan dominance in the region. The wall includes semi-circular bastions at regular intervals, a feature that distinguishes Sirsukh from earlier Taxilan cities and aligns it with Central Asian military architecture.

Unlike the grid-based design of Sirkap, Sirsukh’s internal layout remains largely unknown. Excavations have been limited, with most work concentrated on the eastern fringes near Qila Bani between 1915 and 1916. The city’s interior is still buried under centuries of sediment and vegetation, making it one of the least explored yet most promising archaeological sites in Taxila. Scholars believe that beneath the surface lie residential quarters, administrative buildings, and religious structures that could shed light on Kushan governance, urban life, and cultural integration.

Historically, Sirsukh was built during a time of transition. The Kushans, originally nomadic warriors from Central Asia, had established a powerful empire stretching from Afghanistan to northern India. Under rulers like Kanishka the Great, the empire embraced Buddhism and promoted artistic and architectural synthesis. Sirsukh was part of this vision—a city that embodied both imperial strength and spiritual openness. Its construction marked a shift from the Hellenistic influences of Sirkap to a more Central Asian aesthetic, with emphasis on fortification, monumentality, and axial planning.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Sirsukh is its abandonment. By the 7th century CE, the city had fallen into disuse, possibly due to invasions, environmental changes, or shifts in trade routes. Unlike other Taxilan cities that were gradually repurposed or rebuilt, Sirsukh was left untouched. This has preserved its structural integrity but also limited our understanding of its daily life and civic organization. Theories abound—from pandemics forcing migration from Sirkap to legends of two brothers, Sirsuk and Sirkap, whose names became immortalized in stone—but definitive answers remain elusive.

For modern visitors, Sirsukh offers a unique experience. The site is located approximately 0.5 kilometers off the road to Khanpur Dam, making it accessible by rickshaw or taxi from the Taxila Museum. While the interior is not open for full exploration due to preservation concerns, the outer walls and bastions can be viewed and photographed. The surrounding landscape is quiet and expansive, ideal for reflective walks and historical contemplation.

Sirsukh is especially valuable for researchers interested in urban evolution. It marks the culmination of Taxila’s city-building tradition, transitioning from organic layouts (Bhir Mound) to grid systems (Sirkap) and finally to fortified axial planning. Its untouched state offers potential for future archaeological breakthroughs, particularly in understanding Kushan-era administration, trade, and religious life.

Bhir Mound: The Birthplace of Ancient Taxila

Bhir Mound is the oldest excavated urban settlement in the Taxila Valley, dating back to approximately 800–525 BCE. Located just southeast of the Taxila Museum, this site marks the beginning of organized city life in the region and offers invaluable insights into the early phases of South Asian urbanism. For historians, archaeologists, and culturally curious travelers, Bhir Mound is where the story of Taxila truly begins.

The site was first excavated by Sir John Marshall between 1913 and 1925, followed by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1940s and later by Pakistani archaeologists in the late 20th century. These excavations revealed a complex cultural sequence spanning the Achaemenid, Indo-Greek, and Mauryan periods. The earliest layers of Bhir Mound contain grooved Red Burnished Ware pottery, a hallmark of pre-Achaemenid craftsmanship, suggesting that the site was already inhabited before Persian influence reached the region.

Bhir Mound’s layout is organic and unplanned, reflecting the early stages of urban development. Unlike the grid-based cities of Sirkap and Sirsukh, Bhir Mound grew gradually, with narrow winding streets, irregular building plots, and mixed-use structures. This lack of formal planning offers a rare glimpse into how ancient cities evolved before the imposition of imperial design principles. The buildings were constructed primarily from stone masonry and mud bricks, with wooden beams used for roofing and support.

One of the most historically significant events associated with Bhir Mound is the arrival of Alexander the Great in 326 BCE. According to classical sources, Alexander was received here by King Ambhi, who offered gifts and allegiance. It was from Bhir Mound that Alexander planned his campaign against Raja Porus, making the site a strategic and diplomatic center during one of history’s most famous military expeditions.

Under the Achaemenid Empire, Bhir Mound served as the capital of the province of Hindush. This period saw the introduction of Persian administrative practices, coinage, and architectural styles. Later, during the Mauryan era, the city became a hub of Buddhist learning and governance. Ashoka’s influence is evident in the spread of Buddhist monuments and inscriptions found in nearby areas, although Bhir Mound itself remained primarily residential and commercial.

Artifacts recovered from the site include coins from multiple dynasties, terracotta figurines, pottery shards, and tools. These items are now housed in the Taxila Museum, where they provide context for the city’s economic and cultural life. The diversity of materials and styles reflects Taxila’s role as a crossroads of trade and ideas, linking Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Hellenistic world.

Despite its importance, Bhir Mound remains one of the least visited sites in Taxila. Its understated appearance—low mounds, scattered stones, and partially exposed foundations—belies its historical depth. For those willing to explore, the site offers a quiet, contemplative experience. Walking through its uneven paths, one can imagine the bustle of ancient merchants, the clatter of carts, and the murmur of scholars debating philosophy and politics.

Accessing Bhir Mound is easy. It’s located just a few minutes’ walk from the Taxila Museum and is open daily from morning until dusk. Entry is free, and informational plaques provide basic historical context. Local guides are available for those seeking deeper insight into the site’s significance and excavation history.

Bhir Mound is especially valuable for researchers interested in early urbanism, cross-cultural exchange, and the evolution of city planning. It serves as a counterpoint to the more structured cities of Sirkap and Sirsukh, highlighting the organic roots of South Asian civilization. Its layers of occupation and abandonment tell a story of resilience, adaptation, and transformation over centuries.

Jandial Temple: Echoes of Greece in the Heart of Taxila

Just 630 meters north of the ancient city of Sirkap stands the Jandial Temple, a structure that defies expectations of South Asian architecture. Built between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE, this temple is widely regarded as the most Hellenistic building ever discovered on Pakistani soil. With its Ionic columns, symmetrical layout, and classical proportions, Jandial Temple offers a rare glimpse into the architectural and cultural fusion that defined the Indo-Greek period in Taxila.

The temple’s design closely mirrors that of a Greek distyle in antis layout—a central shrine flanked by two Ionic columns framed by anta walls. The structure includes a pronaos (front porch), naos (inner chamber), and an opisthodomos (rear chamber), all hallmarks of classical Greek temple architecture. The walls are built from solid masonry with pierced window openings, and the entire building is elevated on a platform accessed by a staircase. This elevation not only adds grandeur but also reflects the ceremonial nature of the space.

While the temple’s form is unmistakably Greek, its function remains a subject of scholarly debate. Some archaeologists believe it was a Zoroastrian fire temple, citing the presence of a rear platform that may have housed a fire sanctuary. Others suggest it was a Buddhist or syncretic shrine, reflecting the religious pluralism of the region. The ambiguity itself is telling—it speaks to the cultural fluidity of Taxila, where Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian traditions coexisted and intermingled.

The temple was excavated in 1912–1913 by the Archaeological Survey of India under Sir John Marshall. Despite its weathered condition, the site retains key architectural elements that allow for detailed reconstruction. The Ionic capitals, though provincial in execution, are modeled after the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. The column bases and wall moldings are remarkably pure in design, suggesting that the construction may have been supervised by Greek artisans or carried out under direct Hellenistic influence.

Jandial Temple’s significance extends beyond architecture. It serves as a physical testament to the Indo-Greek Kingdom’s impact on the region. Following Alexander the Great’s campaigns in the 4th century BCE, Greek settlers and rulers established cities, minted coins, and built temples that reflected their heritage while adapting to local customs. Jandial is a prime example of this synthesis—a Greek temple built in a South Asian landscape, possibly serving a non-Greek religious function.

Artifacts found at the site include pottery, coins, and structural fragments that date to the Indo-Greek and Indo-Parthian periods. These items are now housed in the Taxila Museum, where they contribute to the broader narrative of cultural exchange and artistic evolution. The temple’s location near Sirkap also suggests it may have served as a ceremonial or diplomatic space, possibly linked to the elite or ruling class.

For modern visitors, Jandial Temple offers a quiet, contemplative experience. The site is surrounded by open fields and gentle hills, creating a serene atmosphere ideal for photography, sketching, and reflection. While the temple itself is partially reconstructed, its layout and surviving elements allow for a vivid mental reconstruction of its original grandeur. Informational plaques provide basic historical context, and local guides can offer deeper insights into its architectural and cultural significance.

Accessing Jandial Temple is straightforward. It’s located just off the main road leading to Sirkap and is reachable by rickshaw or taxi from the Taxila Museum or railway station. The site is open daily from morning until dusk, with no entry fee. Visitors are encouraged to bring water, wear comfortable shoes, and respect the sanctity of the ruins.

Taxila University: Cradle of Ancient Knowledge

Long before the rise of Oxford or Nalanda, the city of Taxila was home to one of the world’s earliest universities—a sprawling intellectual hub that shaped the minds of philosophers, physicians, grammarians, and strategists. Known as Takṣaśilā Viśvavidyālaya, the University of Taxila flourished from around the 6th century BCE to the 5th century CE, attracting students from across South Asia and Central Asia. It wasn’t a university in the modern sense, but rather a decentralized network of scholars and monastic institutions where knowledge was transmitted through rigorous oral and textual traditions.

Located near the banks of the Indus River in present-day Punjab, Pakistan, Taxila’s university was deeply embedded in the Gurukula system—a residential model where students lived with their teachers, studied scriptures, and engaged in philosophical debate. Initially a Vedic seat of learning, it later evolved into a major center for Buddhist education, especially during the Mauryan and Kushan periods. The transition from Brahmanical to Buddhist scholarship reflects the city’s pluralistic ethos and its ability to adapt to shifting cultural and religious landscapes.

The curriculum at Taxila was remarkably diverse. Students studied the Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas, alongside secular subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, law, military science, and the eighteen silpas or arts. The university was renowned for producing legendary scholars like Pāṇini, the father of Sanskrit grammar; Jivaka, the royal physician of Magadha; and Chanakya (Kautilya), the political strategist behind the Mauryan Empire. These figures not only shaped Indian intellectual history but also influenced governance, linguistics, and medical ethics across Asia.

Unlike modern universities with centralized campuses, Taxila’s learning centers were spread across the city’s monastic complexes—particularly in places like Jaulian and Mohra Moradu. Buddhist monks served as both spiritual guides and academic instructors, and their monasteries functioned as lecture halls, libraries, and laboratories. Students came from distant regions such as Kashi, Kosala, and Gandhara, often traveling for months to study under renowned teachers. Admission was based on merit and recommendation, and the learning process emphasized memorization, discourse, and practical application.

The university’s reputation was so widespread that it found mention in ancient texts like the Jataka tales and the Mahabharata. According to Buddhist lore, even the Buddha visited Taxila during his lifetime. The Mahabharata recounts how Parikshit’s son Janamejaya first heard the epic recited in Taxila, underscoring the city’s role as a cultural and literary center. These stories, though mythological, reflect the reverence Taxila commanded in the ancient imagination.

Taxila’s strategic location at the crossroads of trade routes connecting India, Persia, and Central Asia contributed to its intellectual vibrancy. Merchants, pilgrims, and diplomats brought with them new ideas, texts, and technologies, enriching the academic discourse. The city’s multicultural population—comprising Indians, Greeks, Scythians, and Persians—created an environment of tolerance and exchange that was rare for its time.

The decline of Taxila University began in the 5th century CE, following invasions by the White Huns. Under the rule of Mihirakula, many Buddhist institutions were destroyed, and the city was gradually abandoned. The university’s ruins, now scattered across sites like Bhir Mound and Jaulian, bear silent witness to a golden age of learning that once defined the region.

For modern visitors, the legacy of Taxila University is palpable. Walking through the monastic cells of Jaulian or examining the inscriptions at Mohra Moradu, one can imagine the scholarly debates and spiritual reflections that once filled these spaces. The Taxila Museum houses many of the artifacts associated with the university, including manuscripts, tools, and sculptures that reflect its academic and cultural richness.

Bhamala Stupa: The Cruciform Marvel of Gandhara

Nestled in the serene hills near Khanpur Dam, Bhamala Stupa stands as one of the most architecturally distinct and spiritually evocative monuments in the Gandhara region. Dating back to the 2nd century CE, this Buddhist complex is renowned for its cruciform stupa design, its monumental Mahaparinirvana statue, and its tranquil setting along the Haro River basin. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Bhamala offers a rare blend of archaeological intrigue and meditative ambiance.

Unlike the hemispherical stupas typical of early Buddhist architecture, Bhamala’s central stupa features a cruciform layout—an elevated square base with four staircases projecting in cardinal directions. This design marks a late stage in Gandharan stupa evolution, reflecting both artistic innovation and ritual functionality. The structure resembles an Aztec pyramid in form, with Corinthian pilasters dividing the plinth into bays. Surrounding the main stupa are nineteen smaller votive stupas and chapels, creating a sacred courtyard that once hosted pilgrims, monks, and ceremonial processions.

One of Bhamala’s most extraordinary discoveries is the Mahaparinirvana statue—a 48-foot-long reclining Buddha carved from Kanjur stone. This sculpture, symbolizing the Buddha’s final moments before entering Nirvana, is considered one of the oldest and largest of its kind in the world. Though damaged over time, with its head and limbs broken during early excavations, the statue remains a masterpiece of Gandharan art. Its presence within a long rectangular chamber west of the main stupa adds a layer of solemnity and spiritual depth to the site.

The origins of Bhamala Stupa are tied to the Kushan period, a time when Buddhism flourished across northern Pakistan and Afghanistan. Excavations began in 1929 under Sir Sufiyan Malik and Sir John Marshall, and resumed in 2017 with renewed interest in the site’s preservation and historical significance. The stupa’s cruciform architecture, combined with its monumental scale, suggests it may have served as a regional pilgrimage center, attracting devotees from across the Gandhara Valley and beyond.

Bhamala’s location adds to its mystique. Situated approximately 25 kilometers from the Taxila Museum and perched 400 meters above the Haro River, the site is surrounded by forested hills and natural springs. A nearby cave—still partially unexplored—adds an element of mystery. Some speculate it was used as a monastic retreat, while others believe it may have served political or ritual functions during the Kushan era.

For modern travelers, Bhamala offers a peaceful alternative to the more frequented ruins of Taxila. The site is accessible via Khanpur Road, though the final stretch requires a vehicle with good ground clearance. It’s about a 45-minute drive from Taxila’s main bus stop, and local guides or security personnel at the site can provide historical context and navigation tips. The area is well-maintained, with printed boards offering detailed information about the stupa’s layout, history, and significance.

Visitors are encouraged to explore the site slowly, taking in the symmetry of the stupa, the artistry of the votive chapels, and the quietude of the surrounding landscape. Photography is permitted, and the elevated terrain offers excellent vantage points for capturing the monument against the backdrop of the Himalayan foothills. The site is open daily from morning until dusk, with no entry fee.

Bhamala is especially valuable for researchers and cultural enthusiasts interested in architectural transitions within Buddhist history. Its cruciform design bridges earlier hemispherical stupas like Dharmarajika with later, more elaborate constructions such as the second Kanishka stupa. The presence of the Mahaparinirvana statue also provides insight into devotional iconography and the spiritual narratives that shaped Gandharan Buddhism.

Badalpur Stupa and Monastery: A Monument of Monastic Grandeur

Located approximately 9 kilometers northwest of the Taxila Museum and just 2 kilometers from Jaulian village, the Badalpur Buddhist complex is one of the largest and most structurally elaborate monastic sites in the Taxila Valley. Dating from the 1st to 5th century CE, this site flourished during the Kushan period and offers a compelling look into the architectural ambition and spiritual life of Gandharan Buddhism.

The complex is divided into two primary zones: the stupa area and the monastic quarters. The main stupa, situated on the western side, measures roughly 25 by 22.5 meters at its base and rises to a height of about 5 meters. Though much of its facing stone has eroded, remnants of semi-ashlar and semi-diaper masonry are still visible, showcasing the craftsmanship of Kushan-era builders. The stupa’s rectangular platform is flanked by image chapels and votive stupas, some of which are in poor condition but still retain traces of stucco ornamentation and structural integrity.

The eastern side of the complex houses the main monastery, which spans 81 by 78 meters and includes forty monks’ cells, two gateways, and communal facilities. An additional monastery, discovered during later excavations, lies to the south and features twelve cells, a central water tank, a kitchen, and a storeroom. The walls of both monastic structures are coated with mud plaster internally and stucco externally, with some sections still bearing visible decorative traces. The layout reflects a highly organized spiritual community, with designated spaces for meditation, study, and daily living.

Excavations at Badalpur have yielded a wealth of artifacts, including pottery, gold and copper coins, seals, beads, iron tools, and grinding stones. Among the most remarkable finds is a Mathura-style sculpture of the Buddha, carved from reddish sandstone. The figure is seated cross-legged on a throne, with dharmachakra symbols on the soles of both feet and the right hand raised in abhaya mudra. A pipal tree is engraved behind the figure, symbolizing enlightenment. This sculpture, along with similar finds from Bhari Dheri, suggests that devotees from Mathura may have gifted these images during pilgrimages to Taxila’s sacred sites.

Another notable discovery is a schist stone relic casket shaped like a miniature stupa, believed to have held sacred remains or offerings. A statue of Bodhisattva Maitreya was also unearthed, adding to the site’s iconographic diversity and spiritual significance. These artifacts are now housed in the Taxila Museum, where they contribute to the broader narrative of Gandharan religious art and monastic culture.

Historically, Badalpur served as a satellite institution to larger centers like Jaulian and Mohra Moradu. Its location near the Haro River and the ancient trade routes connecting Taxila to Central Asia made it an ideal site for both spiritual retreat and cultural exchange. The complex’s scale and sophistication suggest it may have hosted senior monks, scholars, and pilgrims, functioning as both a residential monastery and a ceremonial center.

For modern visitors, Badalpur offers a quiet and immersive experience. The site is accessible via Punj Katta Road, off the Taxila-Haripur route, and is best reached by private vehicle or hired taxi. While the ruins are partially restored, they retain a raw authenticity that invites exploration and reflection. Informational plaques provide basic historical context, and local guides can offer deeper insights into the site’s layout and significance.

The surrounding landscape—open valleys, forested hills, and distant views of the Himalayan foothills—adds to the site’s contemplative atmosphere. It’s ideal for photography, sketching, and slow walks through history. Visitors are encouraged to bring water, wear sturdy shoes, and respect the sanctity of the ruins.

Bhari Dheri: The Forgotten Monastery of Taxila

Tucked away in the quiet outskirts of Taxila, Bhari Dheri is a Buddhist monastic complex that dates back to the 4th–5th century CE. Though less frequented than Jaulian or Mohra Moradu, Bhari Dheri offers a compelling look into the final phase of Gandharan Buddhism before its decline in the region. Its remote location and understated ruins make it a hidden gem for travelers seeking solitude, authenticity, and archaeological intrigue.

The site was first excavated in the early 20th century and later revisited by Pakistani archaeologists in the 1980s. It consists of a central stupa surrounded by votive stupas, chapels, and monastic cells. The main stupa, though partially collapsed, retains its circular base and traces of decorative moldings. Built with semi-ashlar masonry and lime mortar, the structure reflects the architectural style of late Kushan-era Buddhist monuments. The surrounding votive stupas vary in size and shape, some featuring niches that once held statues of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

The monastery itself is modest in scale but rich in layout. It includes a series of interconnected cells, a central courtyard, and a small assembly hall. Excavations have revealed remnants of stone flooring, water channels, and storage pits, suggesting a self-sustaining monastic community. The site’s orientation and design indicate it was built for both meditation and instruction, likely serving as a satellite institution to larger centers like Jaulian and Badalpur.

One of Bhari Dheri’s most notable discoveries is a Mathura-style Buddha statue carved from red sandstone. The figure is seated in dhyana mudra, with finely detailed robes and a halo behind the head. This sculpture, now housed in the Taxila Museum, points to the influence of northern Indian artistic traditions on Gandharan iconography. Other artifacts include terracotta lamps, copper coins, and stucco fragments, many of which bear floral and geometric motifs.

The site’s location near the Haro River and its proximity to ancient trade routes suggest it may have served as a retreat for traveling monks and pilgrims. Its relative isolation also made it less vulnerable to the invasions that devastated other Taxilan sites in the 5th century CE. While the White Huns under Mihirakula destroyed many Buddhist institutions, Bhari Dheri appears to have been spared, possibly due to its obscurity or defensive terrain.

For modern visitors, Bhari Dheri offers a quiet and contemplative experience. The site is accessible via a narrow road branching off from the main Taxila–Haripur route. It’s best reached by private vehicle or hired taxi, as public transport does not serve the area directly. The ruins are open daily from morning until dusk, with no entry fee. Visitors are advised to bring water, wear sturdy shoes, and prepare for uneven terrain.

Bhari Dheri is ideal for photography, sketching, and immersive exploration. The absence of crowds allows for uninterrupted reflection, and the surrounding landscape—rolling hills, scattered trees, and distant views of the Himalayan foothills—adds to the site’s meditative ambiance. Informational plaques are limited, so hiring a local guide or consulting museum resources beforehand is recommended.

This site is especially valuable for researchers interested in the late phases of Gandharan Buddhism. Its architectural simplicity, combined with its artistic connections to Mathura, offers clues about the cultural transitions occurring in the region during the 5th century CE. Bhari Dheri also serves as a reminder of the resilience of monastic communities, who continued their spiritual practices even as political and religious tides shifted around them.

Climate and Weather Overview of Taxila

Taxila experiences a subtropical desert climate (Köppen classification: BWh), characterized by hot summers, mild winters, and low annual precipitation. Located at an elevation of approximately 535 meters above sea level, the city’s climate is shaped by its position on the Potohar Plateau, with seasonal variations that influence both tourism and archaeological fieldwork.

Temperature Patterns

Taxila’s average annual temperature is around 32.4°C (90.4°F), which is notably warmer than Pakistan’s national average. The hottest month is June, with average highs reaching 47.7°C (117.8°F), while January is the coldest, with average lows around 10.7°C (51.2°F). These extremes make summer travel challenging for outdoor exploration, especially at open-air archaeological sites like Jaulian and Sirkap.

- Summer (May–August): Temperatures often exceed 40°C (104°F), with June and July being the peak heat months. Despite the intensity, this period also sees the highest humidity and rainfall, particularly in July, which receives about 51 mm of precipitation.

- Winter (November–February): Mild and dry, with daytime temperatures ranging from 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F). Nights can be cool, especially in January, when lows dip below 11°C (52°F).

- Spring and Autumn (March–April, September–October): These transitional months offer the most comfortable conditions, with average highs between 30°C and 35°C (86°F to 95°F), making them ideal for sightseeing and outdoor activities.

Rainfall and Humidity

Taxila receives an average of 23.2 mm (0.91 inches) of precipitation annually, spread over roughly 50 rainy days. July is the wettest month, while December is the driest. Rainfall is typically short and intense, often accompanied by thunderstorms. Humidity levels average around 35%, peaking during the monsoon season and dropping significantly in May and June.

- Wettest Month: July (51.4 mm / 2.02 inches)

- Driest Month: December (2.5 mm / 0.1 inches)

- Average Rainy Days per Year: 49.6 days

Sunshine and Wind

Taxila enjoys abundant sunshine throughout the year, with monthly averages ranging from 8.8 hours in December to 14.7 hours in June. Wind speeds are generally moderate, with June being the windiest month, averaging 17 km/h. These conditions contribute to rapid evaporation and dry air, especially in late spring and early summer.

Seasonal Considerations for Travelers

- Spring (March–April): Ideal for travel. Pleasant temperatures and blooming landscapes make this the best time for photography, hiking, and site visits.

- Summer (May–August): Travel is possible but requires preparation. Early morning visits, hydration, and sun protection are essential.

- Autumn (September–October): Another excellent window for tourism. Clear skies and moderate temperatures support extended outdoor exploration.

- Winter (November–February): Suitable for cultural tourism and museum visits. Outdoor site visits are comfortable during the day but may require warm clothing in the evenings.

Best Time to Visit Taxila: Seasonal Insights for Cultural Travelers

Taxila’s archaeological richness and scenic surroundings make it a year-round destination, but certain seasons offer a more immersive and comfortable experience. The best time to visit depends on your travel goals—whether you’re exploring open-air ruins, attending cultural events, or conducting field research. Based on climate data and tourism trends, the optimal windows are spring (March to May) and autumn (September to November), when the weather is mild, the skies are clear, and the landscape is at its most inviting.

Spring (March to May): Ideal for Exploration and Photography

Spring is widely considered the best season to visit Taxila. Temperatures range from 20°C to 35°C (68°F to 95°F), with low humidity and minimal rainfall. The hills surrounding the valley bloom with wildflowers, and the archaeological sites—such as Dharmarajika, Jaulian, and Sirkap—are bathed in soft sunlight, perfect for photography and long walks.

- Comfortable weather for outdoor exploration

- Clear skies ideal for site documentation and drone photography

- Fewer crowds compared to peak summer months

- Recommended for cultural tourists, researchers, and photographers

Summer (June to August): Manageable with Preparation

Summer in Taxila can be intense, with temperatures soaring above 40°C (104°F). However, early mornings and shaded areas around sites like Mohra Moradu and the Taxila Museum remain accessible. July brings the highest rainfall, which cools the air and adds a lush backdrop to the ruins.

- Best suited for short visits or indoor-focused itineraries

- Hydration, sun protection, and early scheduling are essential

- Ideal for museum visits and shaded sites

- Recommended for determined travelers and off-season researchers

Autumn (September to November): Tranquil and Culturally Rich

Autumn offers a second peak season for Taxila tourism. Temperatures drop to a pleasant range of 18°C to 30°C (64°F to 86°F), and the landscape takes on golden hues. Cultural festivals and local events often occur during this time, adding depth to the travel experience.

- Excellent conditions for walking tours and guided excursions

- Vibrant fall colors enhance the visual appeal of ruins

- Ideal for attending local heritage events

- Recommended for cultural enthusiasts and academic fieldwork

Winter (December to February): Quiet and Reflective

Winter in Taxila is cool and dry, with daytime temperatures between 10°C and 20°C (50°F to 68°F). While mornings and evenings can be chilly, the clear skies and crisp air make it a peaceful time to explore. Sites like Bhamala and Badalpur are especially tranquil during this season.

- Low tourist traffic allows for uninterrupted exploration

- Ideal for museum visits and contemplative site walks

- Recommended for solo travelers, writers, and spiritual tourists

Travel Planning Tips

- Avoid peak midday hours in summer months

- Carry layered clothing in winter for temperature shifts

- Check for local holidays and site maintenance schedules

- Book accommodations early during spring and autumn

Local Food and Restaurant Guide: Culinary Discoveries in Taxila

Taxila’s culinary landscape is a reflection of its layered history and regional diversity. While the city is best known for its archaeological wonders, its food scene—though modest—is rooted in Punjabi flavors, roadside simplicity, and proximity to the bustling eateries of Wah Cantt and Islamabad. Whether you’re seeking a quick bite after exploring Jaulian or a sit-down meal near the museum, Taxila offers a handful of local gems and access to broader gastronomic experiences nearby.

Traditional Flavors of the Region

The local cuisine in Taxila is heavily influenced by Punjabi and Northern Pakistani traditions. Expect hearty dishes, bold spices, and generous portions. Common offerings include:

- Chicken Karahi: A wok-cooked tomato-based curry with ginger, garlic, and green chilies.

- Chapli Kebab: Spiced minced meat patties, often served with naan and chutney.

- Daal Chawal: Lentils and rice, a staple comfort food.

- Roghani Naan: Soft, leavened bread topped with sesame seeds.

- Pakistani-style Barbecue: Grilled chicken, beef, and lamb skewers marinated in yogurt and spices.

Street vendors and small dhabas (roadside eateries) near the museum and railway station offer these dishes at affordable prices. Hygiene varies, so bottled water and freshly cooked food are recommended.

Notable Restaurants in Taxila

While Taxila itself has a limited number of formal restaurants, a few stand out for their consistency and proximity to key sites:

- Royalson Hotel & Restaurant: Located on Grand Trunk Road, this mid-range spot offers Pakistani and fast food options. It’s popular among locals for its biryani, grilled items, and takeaway service.

- Wah Taxila Pizza Fast Food: A small eatery near Hassan Colony, known for its pizza and Italian-style fast food. It’s a casual option for travelers seeking familiar flavors.

Dining Near Taxila Museum

Several restaurants are located within a 10-kilometer radius of the museum, especially in Wah Cantt and Haripur:

- Safari 99 (Haripur): Offers fast food, barbecue, and Pakistani dishes. Known for its flavorful grilled meats and casual ambiance.

- Sadhu’s Retreat & Fossils Restaurant (Shah Allahditta Road): A scenic spot near Islamabad offering Middle Eastern and Pakistani cuisine in a serene setting.

- Tandoori Restaurant (New City Wah): Serves Chinese, Middle Eastern, and Pakistani dishes. Ideal for families and group travelers.

Islamabad Dining Extensions

For travelers staying in Islamabad or passing through, the E-11 sector offers a range of upscale and international dining options:

- Pizza Monger: Italian-style pizza and calzones.

- Xinhua Capital Restaurant: Chinese cuisine with a loyal following.

- The Crown Lounge: Asian and Middle Eastern fusion dishes.

These restaurants are 15–20 kilometers from Taxila and can be reached within 30–40 minutes by car.

Traveler Tips

- Local Etiquette: Most restaurants are family-friendly, but modest dress and respectful behavior are appreciated.

- Timing: Lunch is typically served from 1 PM to 3 PM; dinner from 7 PM to 10 PM.

- Payment: Cash is preferred in smaller establishments; larger restaurants may accept cards.

- Vegetarian Options: Limited but available—look for daal, vegetable curries, and rice dishes.

Accommodation Options in Taxila: Where to Stay Near the Ruins

While Taxila itself offers limited lodging, its proximity to Wah Cantt, Rawalpindi, and Islamabad opens up a wide range of accommodation choices—from budget guesthouses to boutique hotels and serviced apartments. Whether you’re planning a short archaeological tour or an extended cultural research stay, there are suitable options within 5 to 15 kilometers of the Taxila Museum and major heritage sites.

Closest Hotels and Guesthouses to Taxila Museum

- Hotel Royal Palace (Rawalpindi) Located approximately 5.6 miles from Taxila Museum, this mid-range hotel offers clean rooms, courteous staff, and basic amenities. It’s ideal for travelers seeking proximity and affordability.

- Riwayat Guest House (Islamabad) Just 6.3 miles from the museum, this family-friendly guest house is praised for its quiet environment and air-conditioned rooms. A good choice for longer stays or group travel.

- Trivelles Executive Suites (Islamabad) Located 6.5 miles away, this property offers modern rooms, kitchen facilities, and a quiet ambiance. Suitable for business travelers or those seeking a more upscale experience.

- Orange Lake Resort (Khanpur) About 8.4 miles from Taxila, this resort-style property offers scenic views and a more relaxed atmosphere. Ideal for travelers combining heritage tourism with nature retreats.

Budget-Friendly Hostels and Apartments

- Coyote Den Travelers Hostel (Islamabad) A cozy, character-rich hostel 9.3 miles from Taxila Museum. Offers shared spaces, reading material, and a welcoming vibe for backpackers and solo travelers.

- OWN IT – 2BHK Brown Apartment (Islamabad) Located 6.9 miles from the museum, this serviced apartment includes Wi-Fi, smart TV, and a work-from-home desk. Great for researchers or remote workers.

- Bella Vista Hotel Apartments (Islamabad) Offers mountain views, private balconies, and free parking. Located about 8.6 miles from Taxila, it’s a solid mid-range option for couples or small families.

Premium and Extended-Stay Options

- La Maison Hotel (Islamabad) Located 11.1 miles from Taxila Museum, this boutique hotel offers refined interiors and personalized service. Ideal for travelers seeking comfort and style.

- Smart Lodge (Islamabad) Just under 11 miles away, this highly rated property offers clean rooms and reliable service at competitive rates.

- Hotel Le Meridien (Islamabad) A more upscale option 8.3 miles from Taxila, offering modern amenities and business-class comfort.

Traveler Tips

- Proximity Matters: For early site visits, choose accommodations within 6–10 miles of the museum.

- Transport Access: Ensure your hotel offers taxi or shuttle services, especially if you plan to visit multiple ruins.

- Booking Strategy: Spring and autumn are peak seasons—reserve early to secure preferred lodging.

- Amenities to Prioritize: Air conditioning (especially in summer), Wi-Fi, and breakfast options are key for comfort and productivity.

Comprehensive FAQ: Everything You Need to Know Before Visiting Taxila

Is Taxila safe for tourists? Yes, Taxila is generally safe for both domestic and international travelers. The city is calm, with a strong presence of local police and heritage site security. As with any destination, it’s wise to remain alert, avoid isolated areas after dark, and follow local guidance. Solo travel is feasible, especially during daylight hours and peak seasons.

Do I need a visa to visit Pakistan? Yes, most foreign nationals require a visa to enter Pakistan. The process can be completed online via the Pakistan eVisa portal. Requirements include a valid passport, recent photographs, and proof of accommodation or invitation. Processing times vary, so apply at least 2–3 weeks in advance.

What language is spoken in Taxila? The primary language is Punjabi, but Urdu is widely understood. English is spoken in hotels, museums, and by many guides, especially in tourist-facing roles.

How do I get to Taxila from Islamabad? Taxila is about 35 kilometers from Islamabad and easily accessible by car, taxi, or local bus. The drive takes 40–45 minutes via Margalla Avenue or GT Road. Ride-hailing apps like Careem and InDrive are reliable options.

Can I visit Taxila without a guide? Yes, but hiring a guide enhances the experience. Many sites lack detailed signage, and guides can provide historical context, cultural insights, and navigation support. Guides are available at the Taxila Museum and through local tour operators.

What should I wear while visiting Taxila? Modest clothing is recommended. Lightweight, breathable fabrics are ideal in summer. Long sleeves and trousers help protect against sun and insects. In winter, bring layers. Women travelers may prefer a scarf or shawl in more conservative areas.

Are there any cultural etiquette rules I should follow? Yes. Greet locals respectfully, avoid public displays of affection, and ask permission before photographing people. Remove shoes when entering religious or sacred spaces. Tipping is appreciated but not mandatory.

Is photography allowed at archaeological sites? Yes, photography is generally permitted at outdoor sites and in the Taxila Museum. However, flash photography may be restricted in certain galleries to protect artifacts. Always check posted signs or ask staff before taking photos.

Are there restrooms and food options near the ruins? Basic restrooms are available at the Taxila Museum and some larger sites. Food options are limited near the ruins, so it’s best to carry water and snacks. Restaurants and cafes are more accessible in nearby Wah Cantt and Islamabad.

Can I visit all the sites in one day? It’s possible but rushed. A full-day itinerary can cover the Taxila Museum, Dharmarajika, Jaulian, and Sirkap. For deeper exploration, consider a two-day visit to include Mohra Moradu, Bhamala, Badalpur, and Bhari Dheri.

Is Taxila suitable for children and elderly travelers? Yes, but some sites require walking on uneven terrain. The museum and nearby ruins like Bhir Mound are more accessible. Bring sun protection, water, and comfortable footwear for all ages.

Do I need cash or are cards accepted? Carry cash for entry fees, local transport, and small purchases. Larger restaurants and hotels may accept cards, but connectivity can be unreliable. ATMs are available in Taxila and Wah Cantt.

What are the entry fees for major sites?

- Taxila Museum: Rs. 100 (locals), Rs. 500 (foreigners)

- Jaulian, Mohra Moradu, Dharmarajika: Free or nominal fees

- Guided tours: Rs. 500–1500 depending on duration and group size

Can I buy souvenirs in Taxila? Yes, small shops near the museum sell replicas of Gandharan sculptures, postcards, and handicrafts. For higher-quality items, visit artisan markets in Islamabad.

Is Taxila wheelchair accessible? Accessibility is limited. The museum has ramps and basic facilities, but most archaeological sites involve stairs, uneven paths, and open terrain. Visitors with mobility needs should plan accordingly.