The sun had just begun to rise over the Basho Valley, spilling soft light over the meadows and rivers that had lulled us to sleep the previous night. The air was crisp, scented with pine and wet grass. Somewhere in the distance, a river murmured softly — the same river whose echoes had followed us all the way up yesterday through the dust, stones, and danger.

We had reached Basho the previous evening after a day that tested our limits — broken silencers, bruised hands, and hearts pounding from narrow escapes. But once we arrived, the valley rewarded us with a serenity that words can barely hold. Last night, under a sky exploding with stars, surrounded by the sound of water and wind, every hardship seemed worth it.

I had pitched my tent slightly away from the others — closer to the trees, where I could see the sky framed by dark branches. The night had been peaceful, and the gentle whisper of the river was like a lullaby. But now, it was time to move on.

We got up early, eager to bid farewell to this enchanting valley. The morning light danced on the river’s surface, the peaks above glowed golden, and our tents looked like tiny specks of color against a sea of green. Basho was waking up slowly — locals tending to their animals, smoke curling up from wooden cottages, and the smell of parathas drifting through the air.

Breakfast with the Bannu Bikers

Our breakfast was being served — the same comforting spread of eggs and parathas that had fueled us every morning. But today, we had company. Four bikers from Bannu Bikers had left Skardu at four in the morning and made it all the way up here to Basho.

“Meet Amin and his elder brother Jamil,” I said, introducing them to the camera. “And this is Amir Barki and Wahidullah. True adventurers.”

Their faces were still dusty, their eyes red from the early start, but they radiated that unmistakable joy of travelers who’ve conquered a hard road. We shared stories over tea, laughing at how we’d all underestimated the Basho track.

“The track was beautiful, but never again!” Amin laughed. “Next time, I’ll take a jeep.”

We all laughed. The bond between travelers is instant and effortless — no introductions needed, just shared roads and mutual respect.

Breakfast, like always, was simple yet perfect. Eggs fried on a metal pan, parathas glistening with butter, and steaming cups of tea. There’s something about food in the mountains — it’s not just about flavor; it’s about the hunger earned through miles of dust and struggle.

Before we left, we met the local hosts of Nazara Mountain Camping, where we had stayed.

One of them said proudly, “We are the local people here. Our whole family runs this place. Whether it’s summer or winter, we stay here and serve guests.”

“Allah has given us this opportunity,” another added, “to welcome travelers and earn our livelihood through it. People who come here always leave happy.”

And they were right. We were leaving not just satisfied, but genuinely touched by their kindness.

I thanked them warmly. “Your hospitality and food were wonderful. I pray that more travelers come here and experience your place.”

They smiled, “As long as our guests are happy, we are happy too.”

With full hearts and full stomachs, we packed our bags. Standing by our motorcycles, we whispered a short prayer:

Bismillah-ir-Rahman-ir-Raheem.

May Allah make this journey safe and memorable for us.

The Descent Begins

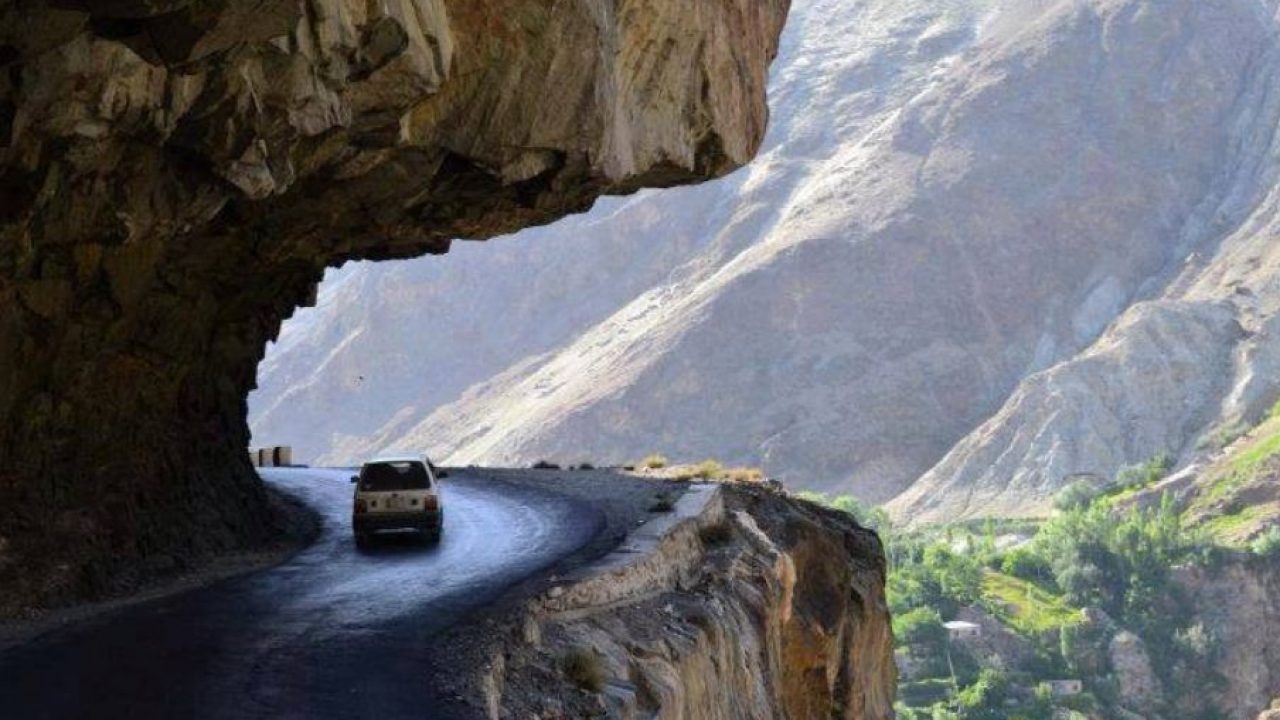

Our first goal was simple — to make it down to the main Skardu road safely. The Basho track was as unpredictable downhill as it had been uphill. The stones that had challenged us yesterday were now our slippery adversaries once more.

Ali started the engine and looked at me. “Let’s hope there aren’t too many jeeps today. It gets tricky when they block the way.”

We set off, riding slowly, the engines echoing off the cliffs. The air was still, the valley quiet. The river beside us shimmered silver under the early sun. I couldn’t help but think how lucky we were to see such beauty — untouched, untamed, and humbling.

There was no cellular coverage here. We had been told that after 15 to 20 minutes of riding downhill, we’d start getting an SCO signal again. Otherwise, you’d have to climb a mountain to make a call. In Basho, disconnection was a part of the experience — a reminder of how small our digital world feels in front of nature’s vastness.

Soon, the first jeeps of the day appeared — loaded with tourists, winding their way up the same treacherous road we had fought through yesterday. We pulled to the side to let them pass.

“Going downhill is just as difficult,” Ali muttered. “Maybe even more.”

The small stones made it hard to keep grip. One wrong brake and the motorcycle could slip like a pebble on glass.

As we descended, we reached a turn where the river flowed violently beside a wooden bridge.

Memories by the Bridge

“Wait, Ali,” I called out. “Let’s stop here.”

We pulled over by the bridge — a familiar one. “We do have some memories with this bridge,” I said, smiling faintly. It was the same one where we had paused on our way up, marveling at the gushing water from Basho’s mountain springs.

The bridge swayed slightly under the pressure of passing vehicles. “Look at that water,” Yasir said, leaning over the railing. The flow was fierce, the white foam colliding with rocks. It was both beautiful and intimidating.

Repair work was underway. Planks of wood and piles of gravel were scattered along the sides. “It’s really swaying,” I said nervously, watching it shift under the jeep ahead of us. “But it’ll hold.”

We crossed slowly, holding our breath until we reached the other side safely.

“Never again,” Yasir muttered. “I can’t imagine doing this in the rain. The grip was already terrible on this dusty road.”

We met the Bannu Bikers again just beyond the bridge. Their laughter echoed across the valley. “How was the ride down?” I asked.

“It was great,” one shouted. “Tiring, but worth it!”

“Let’s get going together then,” I replied. “We’ll go till the main road together, In sha Allah.”

Apricots, Cherries, and Laughter

As we neared the lower villages, the track widened and became easier. “Finally, some smooth ground,” I sighed. The air grew warmer, and the green of the valley deepened into shades of gold.

We passed through clusters of houses, children running behind us, calling “Hello!” and waving. The locals here rode their own motorcycles comfortably — sometimes with two people balancing on narrow seats as they zigzagged along the rocky path. Their skill was astonishing.

We stopped at a small café called Aabshaar Hotel. Its owner, Arif, welcomed us warmly. Behind him, his family was busy picking fruits from the trees. “Wait here,” he said, “I’ll get you something fresh.”

Minutes later, he returned with a basket full of bright orange apricots and deep red cherries. “All from that tree,” he said proudly.

The cherries burst with sweetness; the apricots were perfectly ripe. “You won’t find such good fruit up there,” Arif explained. “The season starts here first. As you go higher, they’re still raw.”

We sat under the shade of a tree, munching fruit, chatting with locals. Everyone we met was kind, gentle, and helpful. I silently prayed that this humility never fades — that tourism, with all its noise and crowds, doesn’t change these people.

Because in their simplicity lies the true beauty of the north.

The Last Curves

Back on the bikes, we tackled the final few kilometers. The track was still dusty and full of blind turns. At one corner, an oncoming jeep forced us to reverse slightly. “Have some patience, can’t you see me reversing!” I called out in frustration. “We’re coming downhill — do you think we can brake on this slope?”

Finally, we reached the last bridge of Basho. It was under repair, planks half-laid, nails protruding. As we rode over it, it swayed violently. “Good Lord,” I said under my breath. “This bridge is dancing!”

The sound of the river roared beneath us, mixed with the creaking of wood. Yasir, whose motorcycle was heavier, crossed carefully, the bridge trembling with every turn of his wheels.

“Adios, Basho,” I whispered once we were safely across. “Next time, we’re coming in a jeep.”

We all laughed, but the fatigue was real. The Basho road had drained us completely — physically and mentally. Yet, as always, the adventure had carved a lasting memory.

Back to Civilization: Skardu

At last, the dusty track merged into the smooth asphalt of the Jaglot–Skardu Road. It felt like freedom — the relief of stability after hours of chaos.

We were finally back in Skardu.

At the hotel entrance, a familiar face waved. “Assalam Alekum!”

“Wa Alekum Salam!” I replied.

“How are you, Abrar?”

“I’m good, thanks to Allah. What about you?”

“You talked to me earlier,” he reminded with a smile. “Where do you want to park?”

“Near our room, if possible,” I said.

“Forget the room,” he laughed. “First, relax. This is your place.”

His hospitality was pure Skardu — warm, effortless, genuine.

The three of us — Ali, Yasir, and I — checked into our room. It was spacious, comfortable, with a clean washroom and soft beds. It felt like a palace after a night of camping and a morning of rough riding.

“It’s 12:30,” Ali said, glancing at his watch. “And hot!”

We decided to rest for a while. Basho had taken every ounce of energy from us.

Afternoon Adventures: The Viewpoint

By late afternoon, when the sunlight softened, we headed out again — not to conquer, but to wander. The locals had told us that the views from the upper ridges were mesmerizing.

We followed a narrow path that climbed above the town. The road was steep but manageable. “If the motorcycle can come this far,” Yasir said, “can’t it go further?”

A local laughed. “You can, but no guarantee you’ll come back down! It’s dangerous up there — only experts try that.”

We parked near a small tea café perched on the edge of a ridge. The view was breathtaking — the entire Skardu Valley stretched out below like a green carpet. You could even glimpse the runway of Skardu Airport. Planes took off so close that you could almost wave to them.

At the café, a friendly old man offered us lassi, pakoras, and tea. “Desi lassi, made from Zomo milk,” he said proudly.

“Zomo?” I asked.

“It’s a cross between a cow and a yak,” he explained. “Our local animal.”

The lassi was light, not sweet — more natural and refreshing. The pakoras were crisp, served steaming with green chutney. Sitting there, sipping tea, watching the sunset over Skardu, everything felt perfectly balanced. The dust, the danger, the exhaustion — all of it melted away.

“This,” Yasir said, “is why we travel.”

Evening in Skardu

As the sun dipped behind the peaks, Skardu transformed. The heat faded, replaced by cool mountain air. The hotel courtyard came alive — soft lights, families dining under the stars, travelers sharing stories. We sat outside for dinner, enjoying the peaceful evening breeze.

“The weather here is just perfect,” I said, taking a deep breath. “It was hot in the day, but this… this is heaven.”

The food was simple — lentils, chicken handi, and warm naan — but the atmosphere made it special. The laughter of strangers, the scent of fresh bread, the sound of the nearby stream. It felt like the heart of Skardu was alive and welcoming.

Later, as we sat quietly, I thought about the journey we had just completed. From the smooth highways of Skardu to the unforgiving dust tracks of Basho; from laughter to fear, from exhaustion to peace — every moment had shaped us.

Travel does that — it strips away your comfort and gives you something deeper in return: perspective, gratitude, and memories that last a lifetime.

Epilogue: The Road Continues

Our plan for the next day wasn’t fixed yet. Perhaps we’d explore another valley. Perhaps we’d rest. But as I looked out over the glowing lights of Skardu, one thing was clear — the mountains weren’t done teaching us yet.

If there’s one lesson Basho gave us, it’s this:

Adventure begins where the road ends.

So, if you ever find yourself in Skardu, take the detour. Ride toward Basho. Face the dust, the danger, the dizzying drops. Cross the swaying bridges, greet the smiling locals, and sleep under the stars.

Because only then will you understand what it means to travel — not just to see new places, but to feel alive again.